Coins and Books

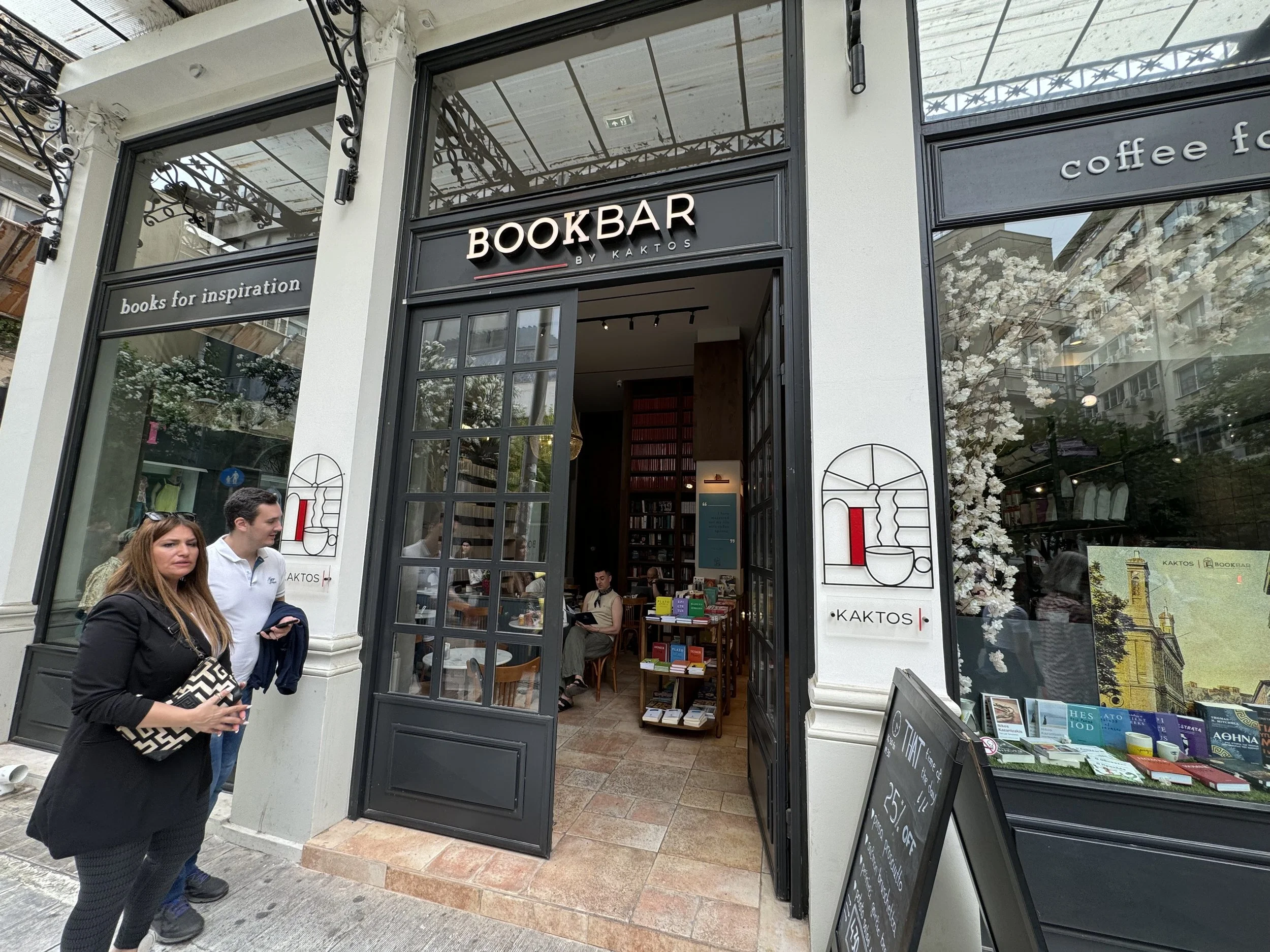

Today, I spent the morning at the Numismatic Museum in Athens. I wrote about the museum two years ago here. Now, I am in the Book Bar near Agia Irini Square, sipping a Freddo Cappuccino and writing this post. It is a charming cafe that sells all types of books in both Greek and English. I think I just found my new office. Coffee, coins, and books. Sounds like bliss to me.

As for the Numismatic museum, I didn’t take a lot of photos this time, which is odd for me, but the museum has not changed and I did not see a need to capture the same displays again. What has changed is my reason for going to the museum. I am searching for coin hoards, in particular hoards that contain coins of the emperor Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180 CE) in order to study wear/use and circulation patterns of these coins and their contemporaries. The museum has one such hoard on display, the Kastri, Attica, hoard recovered in 1952.

Now, to be honest, I do not know anything about this hoard except for the general information provided by the museum. However, what we should note about the display of this hoard is its claimed deposit date or “Date of Concealment:” 1185-1195 CE, and why this is important. Well, it suggests the earliest possible deposit is 1185 CE, but its terminus post quem is 1195 CE. In my humble opinion, this is extremely problematic for many reasons, one of which I will address here. But before doing so, a quick recap of why I am in Athens in order to contextualize why this hoard is important to me.

I am currently researching and documenting hundreds of middle Byzantine and Frankish coins (11th -13th centuries) at the Stoa of Attalos. These coins were excavated in the 1930s from the Athenian Agora and have been paid very little attention since. My goal is to create a larger, more detailed database about these coins, image them mostly with photogrammetry and perform a wear/use analysis. My suspicion, along with a few other scholars, is that the Manuel I Komnenos coins circulated long into the 13th century after the Fourth Crusade and during the Frankish occupation of Athens. My method is situated at the intersection of archaeology, numismatics, digital humanities and statistical approaches to large-scale databases and their metadata. I am using Obsidian.md to create the database, which I have discussed in previous posts and will discuss more in the future when I have permission to publish my work. All that to say, I need hoards of coins to use as a comparison for my wear/use analysis. This approach is drawn from the works of Jean-Marc Doyen, Richard Reece and R.J. Brickstock, to name a few, at the advice of Dr. Guy Sanders, whose knowledge, guidance and insights during our conversations for this project I am very grateful and indebted to.

Coming back to the Kastri hoard and why I claim its deposit/concealment date is problematic is due to the wear on these coins. When you look closely many of these coins, particularly the Manuel I coins, are extremely worn, to the point where many reliefs are difficult to distinguish. The years between the end of Manuel’s reign and Isacc II (the emperor on which the deposit date is dependent, if you do not factor in Issac’s brief 2nd reign from 1203-1204), is only fifteen years. Or, if you use the beginning of Manuel’s reign in 1143 to the end of Issac’s in 1195, we have 52 years. Neither 15 or 52 years is a significant enough amount of time for coins to wear as much as many of these have. Why, you may ask, and what are the implications if we adjust the chronology based on wear?

Well, I don’t want this to turn into a dissertation post, but the short answer is, based on the noted scholars’ works, to get the wear we see in this hoard, and many of the coins I work with, a coin would have been in circulation at the minimum of 80-100 years. This is a low estimate, as Doyen has demonstrated that coins that have extreme wear, basically featureless, were most likely in circulation for 120 years or so. Such chronology would shift the deposit date of the Kastri hoard and who intentionally deposited these coins and why. Indeed, we could propose various scenarios, but a shift of 50+ years in the deposition of this hoard would change its historical narrative significantly. Thus changing how we present such narratives to the greater public. These coins are not just ‘Byzantine’ coins which should be siloed into a narrow historical view. Rather, they are mediums of medieval multiculturalism and economic ubiquity during a pivotal time of transition and change.